Can you tell us a little bit about your background, growing up in isolated landscapes of the West? What was that like? How did your early years inspire your work and practice?

I grew up in Ohio and spent many summers in Lander, Wyoming. I did turn five in Albuquerque, NM and visited Acoma Pueblo that same day. That was my first trip out west and visiting Acoma completely changed my young little life. Experiencing a high mesa with vast vistas, a huge blue sky above, white puffy clouds all the way to every horizon and Acoma Indians wrapped in white robes and blankets was total love at first sight. Going to central Wyoming summer after summer just became an extension of that initial moment at Acoma. I always felt at home in any desolate, quiet, windswept desert. I loved the aloneness in that landscape.

By my teenage years, I became attracted to the rodeo during Pioneer Days in Lander, Wyoming, a week-long event nearby to the Wind River Reservation. For a week, cowboys and their families were in town, Shoshoni and Arapaho were also in town, drinking and wild partying, brawling, cowboys riding their horses into the Union bar — total anarchy for days. This was truly the Wild West. I couldn’t get enough of it. All of those experiences kept me attached to the west. Later in art school, I saw the first of the Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns which eventually became an affirmation that I should paint western subject matter.

About this exhibition, you said Utah is your favorite place on earth. Why Utah?

Utah has tall red mesas, deep red rock canyons, and occasional cottonwood trees. It is all serene, beautiful landscape. The whole Colorado Plateau is almost completely desert. I have an aversion to too much green and mountains that stop at pointy peaks. In contrast, mesas and buttes are mostly flat on top — they completely satisfy my visual aesthetics. There is no place like it on earth. Having visited all of the American deserts and also being a student of foreign deserts (through films) I have come to the conclusion that none of them can compare to the southern Utah landscape.

What inspired your palette for these works?

Nothing inspired my palettes for these works specifically. What inspires me is a constant stretch to keep pushing the limits of color relationships to what I consider to be extreme conclusions. I used to make colors separate very obviously up until the last few years. I began to allow very close values to exist side by side. For example, in “Lone Butte in the Desert” the values in the shadow don’t separate as much as what I might have done 10 years ago. There would have been more contrast in the ground shadows to the foreground sand. There are definitely many more earth tones throughout this body of work than what was evident in past decades.

What inspired you to focus solely on landscape for this body, a move away from your recognizable past figurative and quotable pop works?

I started doing desert landscapes in the late 1990s. I didn’t do them to the exclusion of my figurative work. They sometimes sold and sometimes not. They also weren’t consistently resolved. I’d show one or two in my solo shows and sometimes I just painted them and didn’t show them at all. I began to stack them up and then at some point, Shalee Cooper (Director of Modern West Fine Art) told me how much she loved my landscapes and suddenly the idea (it was Shalee’s) to do an all-landscape show popped up. So I just kept painting them. Over the course of the summer of 2021 it occurred to me that this was going to be my first all-landscape show in my 50-year career and of more than 130 solo shows during that time.

What can you say about Pop art and appropriation? Who are your inspirations?

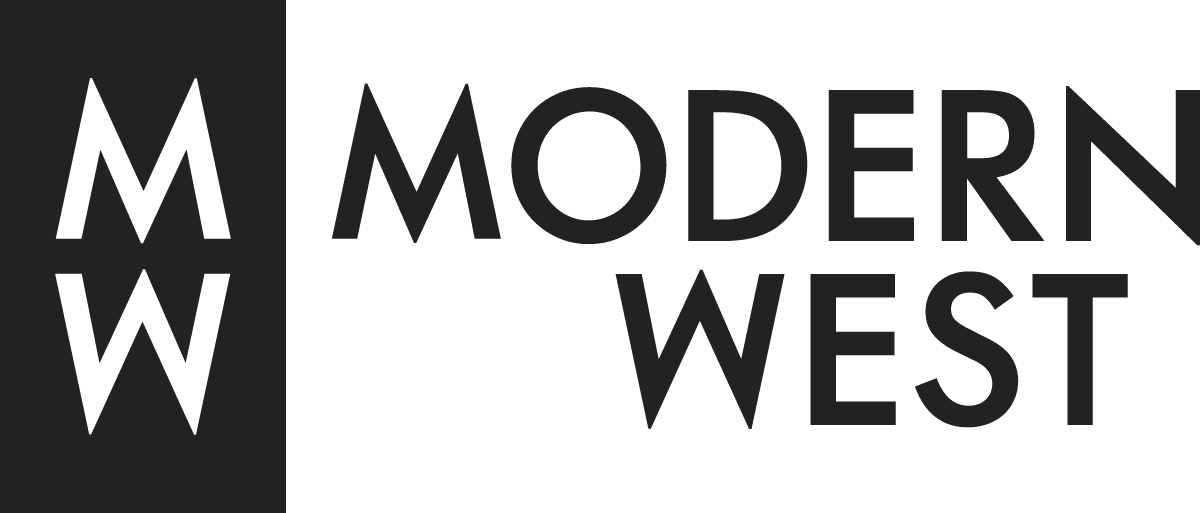

To start with, Pop Art by definition is a school of appropriated images. Since I have an innate inability to draw well unlike almost all the artists in history. I used opaque projectors, overhead projectors and slide projectors to get around that dilemma. Over the years I did just enough original drawing in my paintings to compensate for information that wasn’t there on the projected images. The clouds, for instance, are entirely made up. A lot of cottonwood branches and leaves are too. I never relied much on the local color in slides and photos, especially in the first years exclusively from black and white movie stills. Replicating color from color photographs seemed kind of boring.

Who inspired me. It started with the films of Sergio Leone, the spaghetti westerns from 1964-1970. I wanted to do in painting what Sergio Leone did to the western genre of film. He turned it upside down and totally influenced film-making worldwide. My first direct painting influence in style came from John Clem Clarke. My half-tone dot paintings were influenced by Andy Warhol, the caption paintings by Roy Lichtenstein. The palette and other aspects were influenced by Maynard Dixon, my friend Ed Mell, later on by N.C. Wyeth and another friend Logan Hagege. I had been painting clouds forever but rarely did they feel really resolved until I encountered the huge reductive clouds of Logan’s. I get fascinated by one painter after another, both historic as well as other of my peers, so I ricochet around through all this imagery to try different passages of theirs to see if I can make it fit somewhere in my own work. Leo Dorocher of baseball fame once said “if you ain’t cheatin, you ain’t tryin”. I believed him.

How has your work and outlook on western art and the American West evolved since the 70s, and why is your work still significant to audiences today?

Yes, my outlook or my vision for western art has evolved. At first I was enamored with the ability to transform black and white movie stills into colored paintings on canvas and on a very large scale. It also began (I didn’t realize this for decades) a documentation of my own life. I used friends, lovers, wives, rodeo cowboy buddies, my horses, cattle, etc. as my subject matter. I also documented my own passions and perceptions of the world around me. I began putting all kinds of situations into a western context, just to see what that might look like. By the mid 1980s I painted my first “caption” paintings. I was really concerned about the use of captions because to my way of thinking they were so obviously a reference to Roy Lichtenstein’s comic paintings of the early 1960s. I became more confident as time went on because there was a consistent devious sense of humor to my captions that was distinctly my own voice. I slowly began to formalize a rationale as to what the caption paintings were. I was using them through my mythical characters Cliff, Geoff and Phaedra as metaphors for all kinds of situations that reflected current social and political issues. I like the idea that through these paintings I can raise more questions and simultaneously not reveal any answers. I had become a provocateur. When I was younger I was known as a trouble-maker.

I think my work has remained significant, I prefer to think of it as relevant. The style of my work is completely a contemporary marriage of photo realism and pop. The paint by number look is pure pop as it is referential to the paint by number kits that showed up in the early 1950s. Pop by definition uses commercial art techniques and focuses on popular culture subject matter. The photo realists projected slide images and recreated that slide onto a canvas with paint. They did not edit or change any content. I projected that slide and then reduced the entire image into flat areas of color to create a paint by number look.

Quite often I use multiple slides to create a single image. All that gave my style a very unique look in contrast to the more traditional painterly or illustrational approach to western subject. My subject matter was different. It came from Hollywood movies stills, later from pulp western magazines. My own slides included really tough, capable, sexy, self-assured cowgirls. My cowboys began driving pink 58’ and 59’ Cadillacs, then vintage Rolls Royce’s. My barometer for relevance is seeing that I have a younger and younger audience out there buying my work. That is very encouraging.

What does your work have to say about the American West—the landscapes, the people, the wildness and ruggedness of this place?

I think I said my take on the American West pretty much in Question 6. I will add though, that I have discovered that everywhere in every culture across the globe people of all kinds watch old Hollywood westerns, and have for nearly a hundred years. I think quite often when and if they encounter a western painting that is done in a more traditional approach, it doesn’t register with them at all. If Banksy does something western on the side of the wall in Budapest or Tel Avi they’ll pay attention. It is going to capture their imagination. They might also stop when they see a Schenck painting on a gallery wall. I think that is how I judge relevance.

What’s next for Billy Schenck?

Schenck resolves 28% of the world’s problems and in appreciation becomes richer than Elon Musk.