Can you speak to your background and when you began making art? What influenced you to take up sculpture as a medium?

It's difficult to point to a specific period in my life when I began making art. I believe the line between art and non-art is indistinct and variable.

As far as my background, I grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia. In school, I loved science. My mom was an RN and my dad was a draftsman. At age 14 I started spending my summers working for our neighbor who was a gardener for one of the wealthiest families in the city. The movie The Philadelphia Story was based on this family. They had 33 acres of lawn that we cut. Sometimes we’d spend 8 hours just raking.

In undergraduate school, with more opportunities to explore, I began to take art classes. I gradually shifted my emphasis of study from the sciences to visual art. Robert Rauschenberg was an early influence on me. I loved his use of diverse materials, his formal sensibility, and his idea of acting in the gap between art and life. Although I was trained as a painter, my work has always had a sculptural quality.

In your artist statement, you wrote, “Grafting is a process used to join two distinct plants, often trees, to make them more productive. In my works, these grafted combinations—gangly, elegant, contrived, fragile, and at times self-destructive—are reflections on our peculiar relationship with the rest of the natural world.” How did you come to this practice of grafting? What was the evolution of your sculpture practice?

My paintings in the 80s and early 90s were constructed out of many smaller shaped canvases that were assembled, along with painted wooden elements, to make forms that, in certain portions of the painting, blurred the boundary between the painting and its environment, the wall. I did this using a variety of approaches such as having the canvas taper down to a minimal thickness and then painting that section the same color as the wall. Or I would include a large opening in the center of the canvas and then engage it with a painted wooden element that passed through the space. In some paintings, I used window screen as canvas. The viewer could look at the surface of the painted screen or through to the wall. Drone, an example from this period, is essentially separate from its background except for the transition that occurs in the tapering tail and the doweled “hair” on the top.

Drone, 1983, 60” x 32”, acrylic, canvas and wood

Red, 2002, 50” x 76” x 12”, pine, plywood, mulberry branch, acrylic

Eventually, I found the wooden forms on which the canvas was stretched more interesting than the canvases. And, before too long, I began to include tree limbs. I liked the forms of the branches and I liked the idea of the use of two types of wood that were both different and the same. I integrated them in different ways, such as constructing the wooden forms that the limb wove through, as in the painting Red. I was also becoming more interested in questions of the environment in a larger sense and our notions of the line between humans and the rest of the natural world.

During this time, when limbs were surrounded by but not merged with the processed wood, I was influenced by travel to South America where I saw matapalo trees. The matapalo is a tree-like form but is actually made up of parasitic vines that gradually grow around the tree using it for support. Eventually the tree becomes so covered with vines that it dies but its basic shape, now made of vines, continues to exist.

It was during this time that works such as Table for Darwin evolved. Table for Darwin is a medium-sized table whose top divides into strips and surround a tree branch. This was the first work not attached to the wall; however, I did of think of the tabletop as a horizontal picture plane. Blister, a painting that closely preceded Table for Darwin, may explain my thinking.

The next change was to join the tree limb to the processed wood. This became the Graft series.

Detail of Blister

Table for Darwin, 2004, 29" x 28" x 17", maple and mulberry limb

Your work references many domestic material items like chairs and clothing hangers, but some of your work includes more abstract grafts between branches and hair. Can you discuss the concept and why include hair as medium?

Chairs and clothes hangers are not only objects made by humans, they reflect the human form. Hair is a different, perhaps less abstract, signifier for humans.

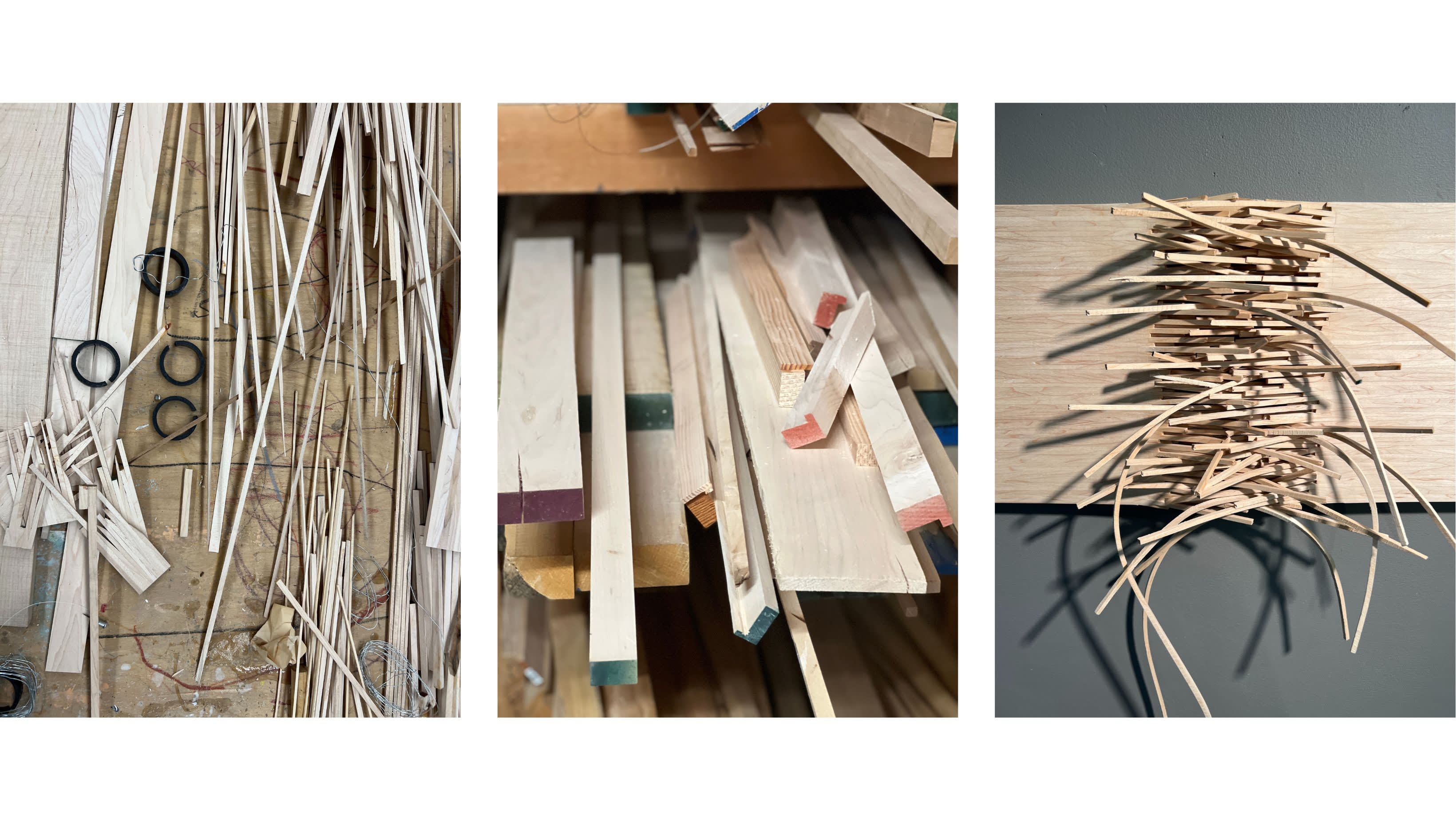

Can you delve into the specifics of how you work? How do you juxtapose the solid wood with the frays? What is the process like for bending that wood?

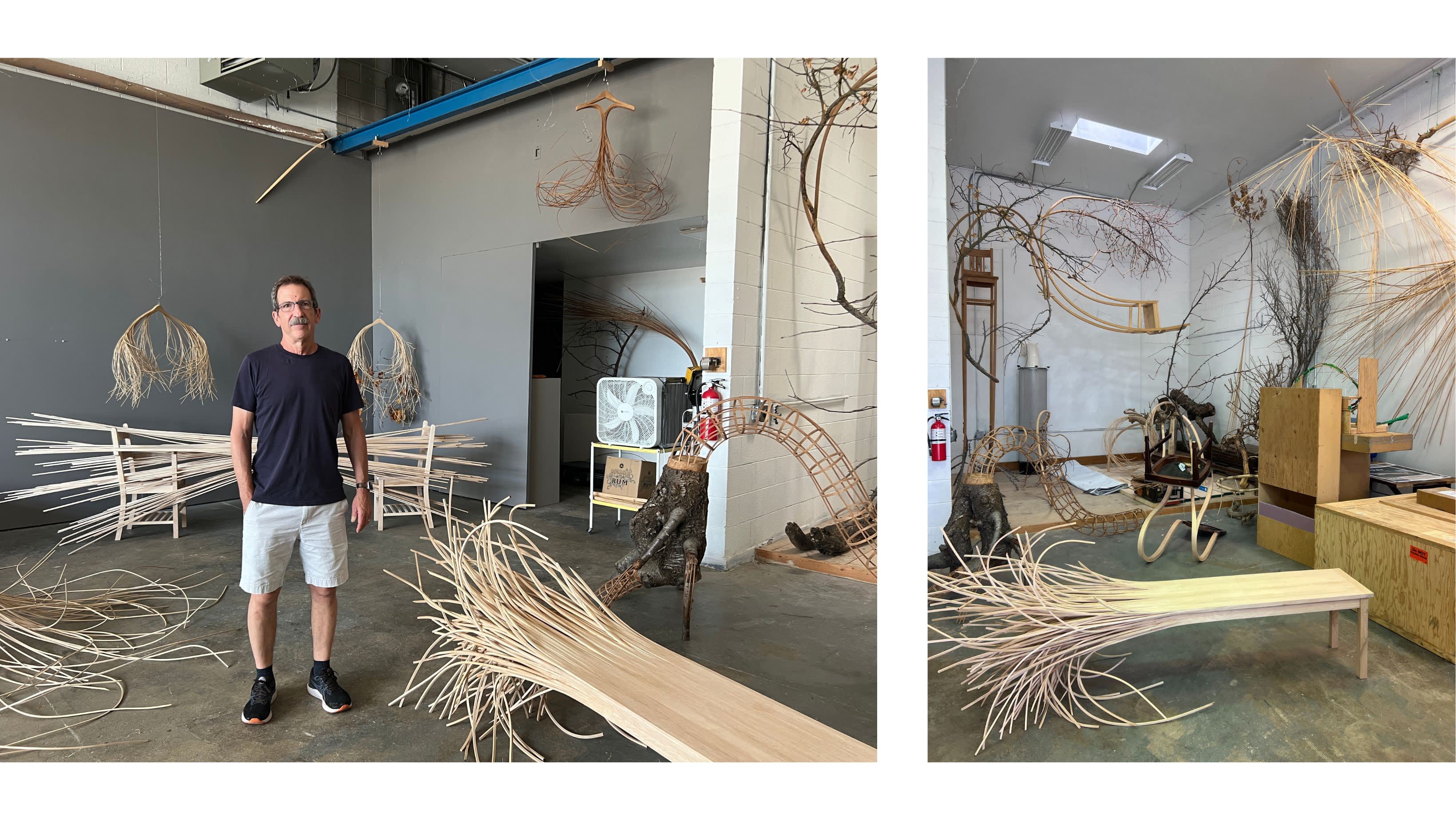

In the series Fray, the juxtaposition is gradual, not discrete. On one end there is a ubiquitous object, a coffee table, a clothes hanger, a baseball bat, a student desk. Gradually, as the object extends downward, or to the other side, unity breaks down and divisions appear. To bend the wood I either laminate thin strips or steam the wood.

How do you choose the type of wood you work with? Is it significant? Do you source it from mills, or do you find it in the landscape? In ‘Table’, for instance — the wood is very unique with knots and angles, it almost looks root-like in structure.

The wood comes from a variety of sources, our yard, construction sites, and mills. The mulberry wood you mentioned in Table is from our front yard. The mulberry branches, especially the older ones, are convoluted. I’ve used a tree stump that I found in a dumpster in Salt Lake. I’ve used wood from a cherry tree tin our yard hat was weakened and killed by shoot hole borers.

The type of wood is always significant but in different ways. I used the trunk of a cherry tree I mentioned above when I built American Cherry, which was, in part, about of the myth of George Washington and the cherry tree. I also used branches from that tree for the legs of Vigilance (chair for James Inhofe) since one aspect of the piece was the idea of weakness and instability. In other works, such as Conversation, all of the wood is from a mill. I didn’t need a specific species, but I did want a wood that was plentiful, sustainable, and that would bend well with steam.

Your works were on view at Museum of Art Fort Collins in the early summer of 2022, and will be on view at Modern West September - November, 2022. What’s next on your radar? Also, how do you transport this work?

Currently I am working on commissions for a couple who are building a new home in Ogden. Sometimes I ship the work in crates, but if the work is large and I need to transport more than 3-4, I will rent a 26’ box truck. I’ve developed numerous cleats, supports, and restraints that I can install in the truck to keep the work secure.

What do you hope viewers see or consider after experiencing your work?

I hope the work is poetic and subversive. I hope it sparks dialogue and discussions among those who see it.