Can you tell us a little about your background and when your arts practice began? What was your childhood like?

I grew up in a large, traditional Utah family. I’m the fifth of seven children, so ours was a noisy house, to which my parents complemented by gifting a home full of music. They are musicians—often practicing and performing together—my dad on the piano and my mom on the violin. At a young age I was struck by how little fear they had in performing. On one hand, I was a fearful child—hesitant to speak up in class and wary of attention. On the other hand, I was eager to take dance lessons. I was slow to learn an instrument but quick to ask my parents for art classes and supplies. Their musicianship impressed my desire to express and create, which took shape more in me by using my hands to create material things. In seventh grade, I remember hand making twenty-five stuffed fabric picture frames for my friends. In twelfth grade I helped choreograph a high school dance concert, and I sewed ten, three-tier skirts for all the dancers. An important and broadening experience occurred when I traveled alone with my father to Washington, D.C. He took me to The National Gallery and Smithsonian museums. My eyes were opened to Matisse’s paper cutouts displayed in a little room at the top of the museum. I was in awe of the shapes he “drew with scissors,” Calder’s floating shapes of color suspended high in the air, and the painting of a girl (who I thought looked like me) standing in a garden by Monet. I began to think about what art is and why people make it—it was the first time I imagined myself being able to create art.

My art practice began just after my fourth and last child was born in 2016—about ten years after graduating with my BFA. I experienced a loss of self and fell into a depression. Becoming a mother pushed me to emotional extremes, having frenzied highs and flattening troughs of emotion—the paradox of wanting my children close but also wanting to escape, all at once. There was a part of me that wanted to die. Having not made much art since college, I turned fully toward it in an effort to ward off the darkness and depression of that state. As I started to create, I found refuge and, consequently, the parts of myself that had withered. I started small with a project called Mothers Hands. I had long taken notice of the monotonous repetition of a mother’s hands, doing the same things over and over again. Eadweard Muybridge’s motion photography work from the 1880’s inspired me to adopt the concept in order to illuminate, animate, and give meaning to such repetition. About twelve of my friends “loaned” me their hands for the project in what has become a central theme to all of my work: using and making objects to memorialize a feeling.

Your new body of work created while in residency is titled 'RE/PLAY' and references childhood, exploring “the delight that comes when we allow ourselves to exist outside pressure to be productive – and just play.” For you, what does 'pressure to be productive' look like? What does 'play' look like?

The ‘pressure to be productive’ is wrought by looking at the to-do-list and a full calendar hanging on the

fridge, imposed by the incessant demands of my phone. Play is being absorbed in making, creating, and experimenting with my hands–losing track of time.

Becoming depleted, in a way, refuels me. It permits a healthy way to deplete and re-energize. I attended a two-week ceramics workshop this past summer where I worked in the studio for over twelve blissful hours a day, and I still couldn’t get enough. I kept thinking, is this what it was like to play when I was a child? I think that the intuitive creativity of childhood becomes a stranger to adults, and play allows me to rediscover and engage with that. True to form, my floors are littered with toys—especially blocks, Magnatile and nerf gun bullets. These small construction projects of scattered shapes come and go without much of a visual record. They began catching my eye for their potential artistic value. Interesting compositions emerged as I began photographing them to keep a record of what I found engaging, and questions came about of how to preserve these thoughts and feelings instead of the stuff itself, along with questions of what compelled me to do so in the first place.

Who are you inspired by? What books are you reading, or what podcasts, music, or media are you listening to and watching?

I love classical music and jazz—especially Astrid Gilberto and Dave Brubeck. The Toast Podcast and My Family and Other Animals are some favorites. I relish time reading art books about my favorite artists. At the moment, they are: Mahaly-Nagy, Sophie Taeber-Arp and Eduardo Chillida. My kids and I love the book Toy Stories: Photos of Children From Around the World and Their Favorite Things by Gabriele Galimberti. Sitting on my side table at the moment is What Artists Wear by Charlie Porter.

What has your experience been like raising kids and also practicing art professionally? What is the give and take there — between making time for your family’s play and your personal practice (and play)?

One informs the other. One fuels the other. This tension is what drives me to create. To say what I have to say visually, which I can’t express any other way. Watching my kids play has been the inspiration behind the project RE/PLAY. This past year, I gave them the book Kids’ Paper Airplane Book by Ken Blackburn. I was enamored with watching them build and fly them, over and over again. We started making and flying them together. There is a window of time when a child plays on repeat, all day every day, without inhibition. They build with blocks and legos, then knock them down—it’s like pushing the “repeat button.” This starts to change as they get older. My work with RE/PLAY seeks to record, sustain, and build roads between the creative intuitions of children and the decline of such in adulthood.

Stepping away from making art for ten years while having children made me starved for it. During those years I did lots of looking. I looked at art all the time, storing up ideas to develop later. The take is that being a mother of four makes every minute seem like one that needs to be put toward something of meaning—toward them or toward my art, but summoning the energy to do that can be difficult. The give is that I’m constantly reminded that the urge to play and create wanes with age, and my family provide me oftentimes with the starting point for actual content and oftentimes the drive to call up that energy and

follow through with my ideas.

What has your process been like while in residency at Modern West? Can you walk us through how you make your relief images and cyanotypes? Do you make those paper planes referenced in your work?

I’m new to printmaking, but I started working on a previous project at SaltGrass Printmakers and fell in the love with its many possibilities. I began experimenting with relief printing–or what is also referred to as “blind embossing”—where no ink is used, just the press applying the pressure of a shape or object into paper. This process embodies what a footprint on the mind or a memory might literally feel or look like: experiences or moments being impressed in the mind. My work obsesses over the idea of preservation. What we, as humans, preserve, why we hold on to things and experiences, tangible objects or memories in the mind, and what that actual memory might look like hanging on a wall, to be felt and experienced again and again—not the object itself, but the feeling of the thing or memory.

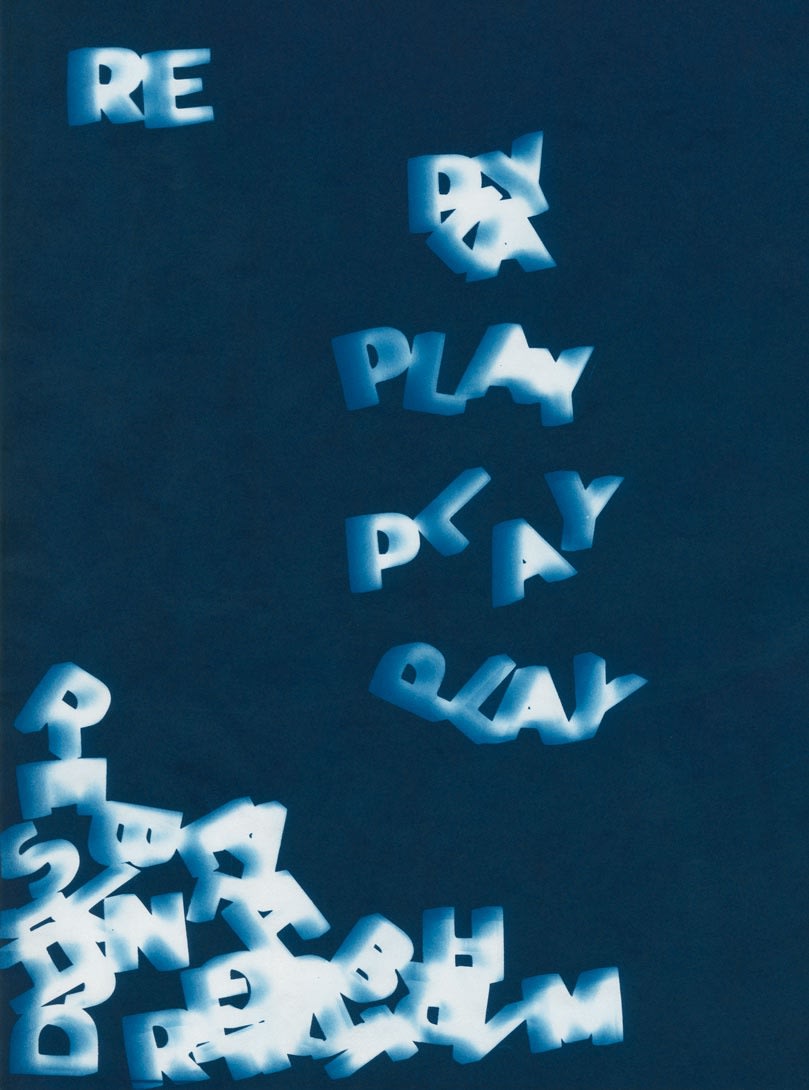

I worked between the studios at Modern West and SaltGrass. I experimented with different types of paper and handmade paper to achieve a three-dimensional effect, creating a fossil-like record of play. After studying Mahaly-Nagy’s photograms this year, I wanted to use light and shadow to preserve objects that reference play—in a way painting or traditional photography couldn’t capture. The photogram is also known as the technique of cameraless photography.

The photogram communicates both “the outer form of things and their inner structures.” It is this idea of seeing the internal space of an object or memory—the artistic equivalent to X-ray photography—that I wish to convey through my work, to see the opaque versus the transparent in a visually tangible way, using light. The photogram does not require a darkroom and is relatively easy to control using direct sunlight. The light sensitive chemicals are applied to paper then exposed in direct sunlight. I used actual toys (nerf gun bullets, blocks, paper airplanes), as well as traced shapes of toys and cut-out silhouettes of paper. I experimented with moving the shapes during the exposure to create a layered, multiple exposure effect, shapes echoing each other in shadow or light. The paper airplanes created subtle shifts in value depending on the number of folds in the paper. This led to an exciting interplay between light and dark, positive and negative, that articulated my paradoxical feelings about parenthood. It’s like experiencing a quiet or controlled chaos or finding a middle ground or coexistence between two opposing viewpoints.

Who do you hope your work reaches? Do you have any advice for anyone looking to escape the construct of productivity return to play?

My work reaches anyone that has forgotten what it was like to play as a child or had childhoods that didn’t necessarily make room for play, whose parents couldn’t or didn’t foster that environment–fully or otherwise. In Stuart Brown’s book, Play, he shares a story about a child whose parents didn’t allow him to play. This child grew up to be the cause of tragic violence towards others. While this is an extreme example—though, sadly, not too extreme—I do think that being severed from the type of play to which children have innate access can also sever us from the abilities that it enables, the ability to make friends with whomever is around, the ability to imagine, tell stories, and create worlds from whatever objects happen to be within reach. Focusing on productivity alone can wear down, blunt, and distort the emotional experience; it can create a distorted sense of what’s important and generate anxieties out of essentially meaningless and trivial things. RE/PLAY encourages us to play, to think about play, and it, in a way, literally makes time. It’s interesting: many of us forget how to play as we get older. RE/PLAY brings to light the astonishing process in which a child explores and experiments with no thought of trying to be productive. It reminds us to keep playing.