Art is play.

It’s also work, hard work: work so challenging many people assume they can’t do it. But that’s because they think it’s nothing but work. Better they thought it was play.

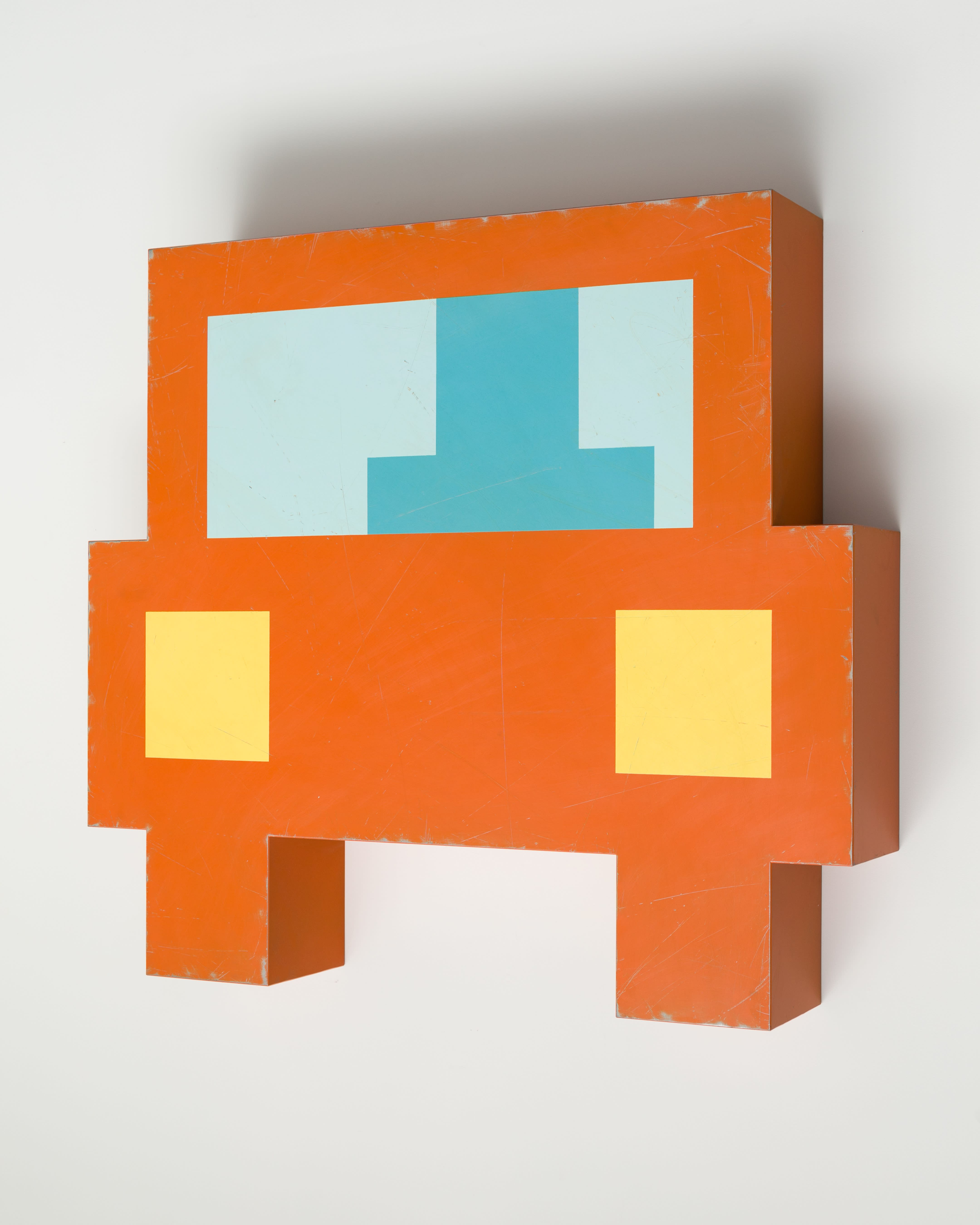

To be sure, Mike Whiting works very hard on his art. The precision demanded by one of his vehicles, the cutting out of the panels, and from them their windows and doors and the pieces that go inside that must fit perfectly, is not something everyone could do. Just as not everyone could fold a piece of paper into a perfect origami crane.

But that’s craft. Building a small car or truck from steel or folding an origami crane are crafts, extreme immersions in reality.

But art isn’t reality. It’s make-believe. It’s play.

Under the leadership of Diane Stewart, it’s not only artists who play at Modern West. Recently, the staff have toyed as well with the conventions of the gallery, where they have taken to dispersing some of the art works it holds among its variously functional spaces. No Brakes, their current exhibition of Mike Whiting’s automotive–themed art, fills the perimeter of the second floor, so that some of the more innovative pieces are viewed from among a fictional landscape made of tables stacked with art books, which become like the city blocks through which the miniature trucks and cars navigate. The distant vista in turn comprises colorfully painted relief sculptures, hung on the walls like canvases, though they could as easily be stood on pedestals. Here Whiting also plays with gallery conventions. Viewers risk overlooking “Building Three,” which backs up the four pedestals on which the vehicles are shown and ambiguously alternates between part of their urban scene and a fifth, empty pedestal.

Artists only know so much about their work. Up to a point, the artist is not just an expert; the artist is the expert. But beyond that point, anyone can know as much as the artist. Maybe more. Anyone, even a child. When Mike Whiting compares his undeniably three-dimensional sculptures of automobiles and buildings to the flattest of things — to the digitalized images of computers, which are electrical concepts and have no depth, he refreshes ideas like thin, thick, shallow, and flat with new perspectives, much as a computer refreshes its screen with light. But hand his sculpture of a truck to a child and watch it become so much less, and yet so much more: a real truck of the hand and the mind.

Spread around the walls, meanwhile, are the repurposed hoods of four performance automobiles and five shallow steel boxes, all nine of which duplicate in various ways the function of stretched canvases. The geometric patterns some of them sport, painted in automotive enamels, diagram patterns of lines that invoke speed, even while tracing so many interacting routes that contrast with static rectangles that locate the cars that traverse those theoretical avenues. Their titles succinctly identify the actions they entail. “Plume” replicates a jet of water or a drag racer leaping from the starting line. “Day’s End” presents the checkered flag that ends that race. In between, “Figure 8,” “Road Signs,” and “Split Junction” move the action along while “Drift” captures the thrill of a four wheel slide. “Harness,” the one seemingly static reference, reveals how the web of wires that seem passive are alive with electrical energy.

When Whiting writes, in his statement, that “video gaming and minimalism arrived at the same visual conclusion through different means and by opposite intentions,” he’s brilliantly showing off the genius of visual thinking. Here, in a variety of single objects, he dives deep into two sophisticated and abstruse subjects and, in their intersection, finds an accessible truth about them both. That accessibility is what makes art indispensable. Artists simplify overwhelmingly complex reality, even turning it into child’s play. Every work of art is an abstraction from the original that was found in reality.

Not every work of art is as abstract as Mike Whiting’s “Signal”: three stacked squares, red, amber, and green: Stop, Caution, Go. But the idea of every real stoplight is found right here. Hung on the wall, where they become low reliefs, works like “Signal” and “Car Demon” confront us, representing the mundane, daily danger of encountering countless unknowable strangers — like so many anonymous riders who might easily hurt us — yet hoping to pass harmlessly by.

And finally, there’s something magical about Whiting’s discovery that children’s toys and primitive computer graphics can be synchronized in the way he does. Both, after all, have to do with setting forth. Children had to learn to walk before they could run, and so did computers. Here again, nightmarish fears that computers will one day overtake their makers and become their masters are conveyed in the image of play, a culture replicated and elaborated in so many toys.

Mike Whiting: No Brakes, Modern West Fine Art, Salt Lake City, opens June 17, 6- 8 pm; through Aug. 31

Geoff Wichert has degrees in critical writing and creative nonfiction. He writes about art to settle the arguments going on in his head.